This is an extract from “Understanding the social impacts of the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme”, research and analysis on the first two rounds of the Mayor of London’s Crowdfunding programme with Spacehive. Read the full report here.

Communities are at the centre of the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme, which is primarily an initiative to enable Londoners to be part of regeneration through meaningful involvement in the bottom-up development of the city. With campaigns developed and put forward by pre-existing community groups or through especially established organisations, the Programme is playing an important role in bringing people together over a shared interest in improving their locality, whilst crowdfunding a project itself acts as a new method of participation, with, in one case, more than 900 people engaging in a project through the crowdfunding process.

Of the sample of project groups used for this research, four were pre-existing community groups, two were off-shoots from existing groups and one was an entirely new group created around a new idea for the locality. These differences appeared to have a limited impact on the extent of community reach and engagement for the respective projects, which instead seemed to align more closely with either the reach of core group members, the capacity that core group members had around campaigns and social media, or the type of project. This was best illustrated by the reach of a community centre project, a market project and a park project, each of which, by their nature, more significantly transgresses individualistic interests and as such appeared to encourage greater levels of participation. Generally expansion into respective communities has been good and assisted by the crowdfunding process whose success requires a strong following and high levels of community support, with one group noting that prior to the Programme their group had “never really engaged” and was “really inward looking”. More recently, they note they have entered a new phase of “incredible engagement”, linking up with the local interest society, local businesses, and a wide range of other interested organisations and individuals. This pattern was replicated across groups with another stating:

“We spent about 3 months engaging and building up a relationship with the community; getting people involved, making partnerships and so on. So when we launched our first Crowdfund

[…] lots of people were behind us and part of the project.”The above example also exemplifies the role of building awareness in the community, which encourages both acceptance and further involvement, either through pledging or through direct action with a project group. One group noted that awareness building was central to the growth of their project group, and its expansion into different, lesser known parts of the wider locality and its residents:

“Local people caught wind of the project through the media and social media and started emailing asking how they could get involved and make it happen, and before we knew it we had 200, 300 emails from willing volunteers”

The process of awareness raising and building a successful project campaign which involved sharing project developments with the local community appeared to be central in building a cohesive community that came together behind a project. For one project situated within a very mixed community, building community cohesion was less about the crowdfund itself, and rather focused on strong communication surrounding the project’s aims, its funding streams, and who its delivery was ultimately for. Whilst noting the project was first met with some hostility due to “money being put into something that doesn’t necessarily make life easier in an area where some people are struggling to survive” , through communicating the financial sources of the project and the long term aims of the redevelopment, as well as hosting activities for the surrounding community that drew on the shared history embedded within the area, the project group was able to appease and integrate members of the diverse surrounding community. Ultimately, they noted:

“It’s been so great to be part of something that’s brought so many different types of community together … these people are people who have been here their whole lives and they can see this is for them, and they can be part of it.”

Beyond resident to resident engagement, projects delivered through the Crowdfunding Programme play an important role in catalysing partnerships with and between local businesses, as well as the local council and Councillors. This is significant in its longer term impacts for the redistribution of community power and capital (see Dahl 1960). This effect comes both through the crowdfund process in which dominant groups or organisations can and tend to support successful projects, as well as through face to face interaction and verbal offers of support. As one group put it whilst referring to the wealth of community and financial support they’d received: “we have confidence in our voice as equals at a table that would otherwise be incredibly power laden.” Arguably, this is akin to the weight of a well-signed petition. Undoubtedly, this claim to legitimacy is greater where those involved (rather than just benefit as in the example above) are varied and diverse, encompassing a broad conceptualisation of ‘community’. However, participants themselves are quick to point out that reaching the ‘hard-to-reach’ is still a difficulty, even in bottom-up development methods.

“There’s a self-selecting crowd who are just the same as us [young, white, middle-class], who are super engaged and that kind of stuff and will actively come along to things […] but we know for the project to be successful we have to be inclusive.”

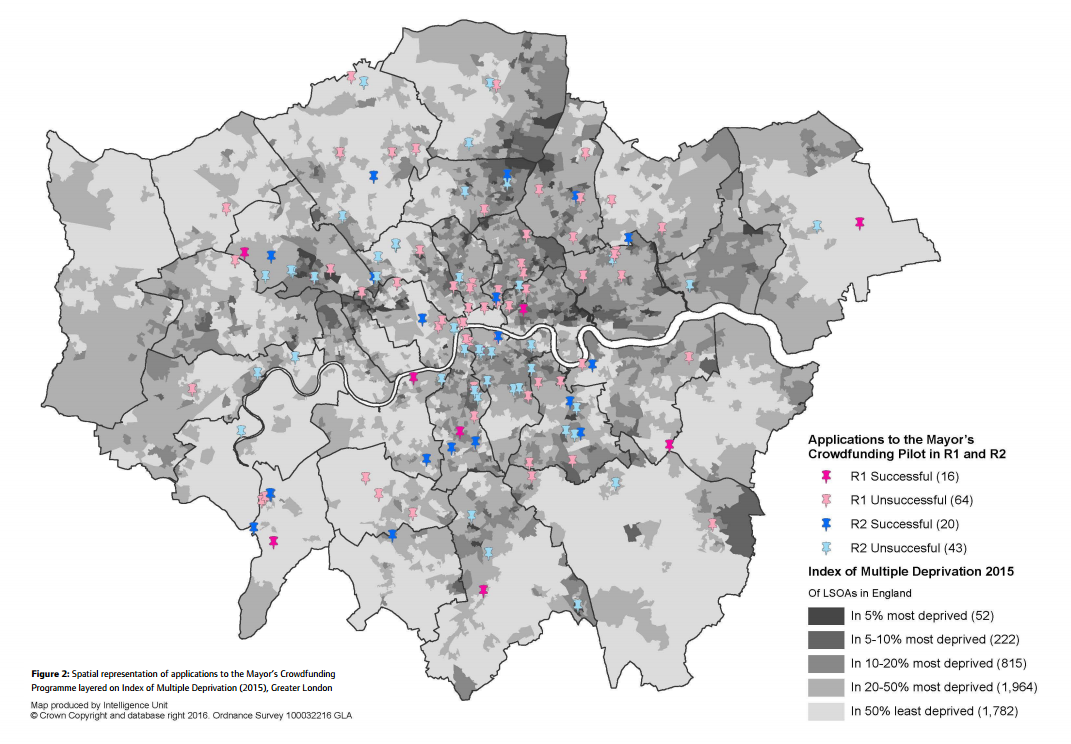

In an attempt to address the issue of diversity, one group made entirely of “white middle-class mums” specifically put a call out for involvement from the large Asian population in the area, yet had no uptake from members of this group. Another noted the importance of working with Tenants and Residents Associations and other pre-existing groups with a diversity of members, though too made it clear that this was more difficult than had been anticipated. Throughout the research process, all project leads and participants met by the researcher were white, and based on proxies such as education level and occupation; all were considered to be of a higher social grade (B or C1). No participant appeared to fit into D or E groups. This may be compounded by the geographies from which applications to the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme come from, illustrated spatially in figure 2.

Thus, whilst community engagement in the delivery process offers new and engaging ways of participating in planning and regeneration, and effectively brings communities together over a shared interest, there is inevitable bias in those who are directly involved and who pledge to projects, despite attempts by project groups to overcome it. As one group reflected:

“The crowdfund worked here because of the environment we live in. It’s a small community, it’s affluent, there are high net-worth individuals, and there’s a lot of pride in where we live”.

This market-led outcome of the crowdfunding process then, indicates a pressing role for GLA Regeneration and public bodies moving forwards with civic crowdfunding: A greater emphasis should be placed on supporting underrepresented groups in their applications for public funding, assisting with capacity building and providing increased light-touch support prior to the project selection process. Without these types of government support in growing the number of applications from areas of deprivation and more deprived groups, there is a potential for civic projects delivered through a crowdfunding process to operate within a ‘civic echo chamber’ due to group homogeneity, making the potential of a false presumption of widespread and diverse support (such as 900 backers) a possibility. This links to a wealth of literature that considers tyranny in participatory decision-making (see Cooke and Kothari 2000). Indeed mySociety note of digital democracy “if tools are predominantly being used by a homogenous group already dominant in society, this has the potential to skew … practical interventions in favour of this dominant group, at the same time compounding disadvantage amongst less dominant groups in society” (2015:19).

This, when considered in the civic context of this research reasserts and develops Centner’s (2008) claim that certain groups can draw on their privilege to dominate space in a time of changing civic norms and tastes through use, and demonstrated here through development (see also Bell and Jayne 2010). Arguably, without an active local government presence in the crowdfunding process, to monitor diversity of project groups and their supporters, those with a quieter voice within spatial conflicts and contested civic norms will see their opinions absolved.

Despite potential problems regarding the homogeneity of backers or applicants (or perhaps resulting from it), the nature of engagement that the crowdfunding process requires and, subsequently the type of community that is more likely engage with it helps address a significant issue in local government and urban development democracy: It seems to appeal to a demographic that may be younger than those traditionally engaged, and as such are unlikely to be homeowners . Tenure has long been considered a significant issue in planning participation discussions, with homeownership considered a key motivation to participate in civic decision making, though, it is also noted that homeowners tend to be more individualistic in their activity (Lundqvist 1998). Indeed, a 2015 GLA publication on participation in matters of the built environment revealed that NIMBYism was a significant driver of participation in civic matters because of home owners’ more long-term attachment to place. Whilst young renters who engage with the Mayors Crowdfunding Programme’s projects may still be of a higher social grade and be politically minded in their careers and social lives, their involvement in urban redevelopment is significant.

Clearly crowdfunding catalyses people within divergent communities to come together for positive collective change, rather than through individualistic motives. This is to a much greater extent than traditional grant based funding for projects due to the social engagement required to grow project finances. However, reaching the hard-to-reach or less dominant groups remains a challenge.

Note: Though ages of project leads and group members in this research are mixed, online research of applications and nonparticipant observation at Crowdfund London events run by the GLA are both indicative of a younger demographic than in traditional planning and regeneration participation meetings.

Read the full report “Understanding the social impacts of the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme” here.