This is an extract from “Understanding the social impacts of the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme”, research and analysis on the first two rounds of the Mayor of London’s Crowdfunding programme with Spacehive. Read the full report here.

Unsurprisingly, those who deliver projects funded through the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme undergo an extensive journey of capacity building throughout the process. For many, it may be their first experience of project management, regeneration and planning, finance and budgeting, campaigning, and indeed crowdfunding. As a result, the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme presents opportunities for participants to develop personally and professionally.

Beyond the immediate impacts of growing skills and knowledge, building capacity has three major knock-on impacts. Firstly, it helps the sustainability and longevity of the projects, best illustrated by a project lead who, as a method of sustainably raising funds to sustain the project in the long-term, instigated a grass-roots Business Association. Working in a similar way to a formal Business Improvement District (BID), 22 businesses on the high street now pay £60 per annum in to a common fund which is used to maintain different elements of the project and pay for community events. Standard critique of (BID) errs caution regarding an imbalance of power between individuals, community groups and larger, profit driven organisations, which may cause a disruption in the heterogeneity of the production of space as discussed by Lefebvre (1991). However, in this case, the local and grass-roots element of the association, managed by the community group, should provide a sufficient barrier to this, and moreover, enables local business to have a voice in their area’s development.

Secondly, skills improvements can have real impacts on career progression and transformation. Almost all participants referred to the programme as having a positive impact in their career, with several including the management of the process on their CV and in career based discussions. One participant revealed that one of her project teammates had recently been offered a job in an entirely different industry to his previous one as a result of the work. She then followed this up by detailing how the project was opening doors for each individual involved. Outside of formal employment for several years, another participant noted that her Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme project had become a central part of her job applications, with the skills granting her greater confidence in these applications. Though yet to find a position, she stated:

“I’ve raised £100,000 from various sources in a year

[…] I know this project is helping me.”Thirdly, developing knowledge of the regeneration and the planning process has been a significant impact of many projects, as well as being integral to their success. In a planning system such as England and Wales’, characterised by multiple layers and piecemeal decision making rather than hard and fast ‘rules’, knowledge of it is integral to effective participation (GLA 2015; Irvin and Stansbury 2000). Since knowledge enables participation, and participation in turn democratises the planning process, this impact should not be overlooked. As noted in the Borough of Southwark:

“A lot of people are getting more attuned to planning and regeneration as a result of this. They’re […] understanding what it means to them, learning how things should be done and commenting on applications or going to community forums.”

Whilst this example (of many) should not be understated, they do have the potential to fall victim to the concerns outlined in literature that discuss group homogeneity or the problem of ’usual suspects’ – even where this might be made up of new individuals (see mySociety 2015; Brent 2004; Campbell 2005). This has been overcome by one project group, whose monthly market always has a table for the local interest group, representatives from which answer questions and educate shoppers – thus reaching beyond project participants into the wider community – on planned changes to the area, and how they can be involved in the process. She added:

“Councillors have also come down to their stall to chat to people. It has become a centre for education and community power in that sense”.

Though a multitude of skills and knowledge can evidently be gained through taking part in the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme, a certain capacity is required to get started, which may cause disparities in the applications that emerge on the Mayor’s Hive. The two most significant of these capacities are some level of political engagement or governance knowledge, adeptly highlighted by three project groups who were approached by local Councillors with the idea of starting a campaign on the Mayor’s hive; and some grasp of technology: ultimately being ‘online’. These barriers to partaking in the Programme as it is currently run could be addressed by additional support from the Regeneration Unit. Yet, beyond these, more specific skills can be integral to running a successful campaign. A pre-existing understanding of social media, project management, and finance was cited by all participants as integral to their success, with one discussing the ways in which team members’ past careers in law, accounting and local government enabled the smooth running of the process, and meant ironing out mistakes quickly. Another spoke of the benefit of having a range of professionals in their team, making the process “iterative” and one where the team was “constantly learning from each other”.

This knowledge sharing is undoubtedly a positive element of the programme and is akin to crowdsourcing skills, however it raises equity issues. Without these skills – more likely to lack amongst deprived groups – the time cost of attempting to manage a community-based regeneration project may be too great to be viable. This issue may be worsened by the increased likelihood of those from deprived groups working unsociable hours and having less leisure time overall. Indeed, of the participants in this study, four worked service sector office based jobs, whilst of the other three, one was a housewife, one was retired, and one was the owner of an SME. Limits of this sample are noted, but further scoping is required to see whether this pattern follows across all successful groups.

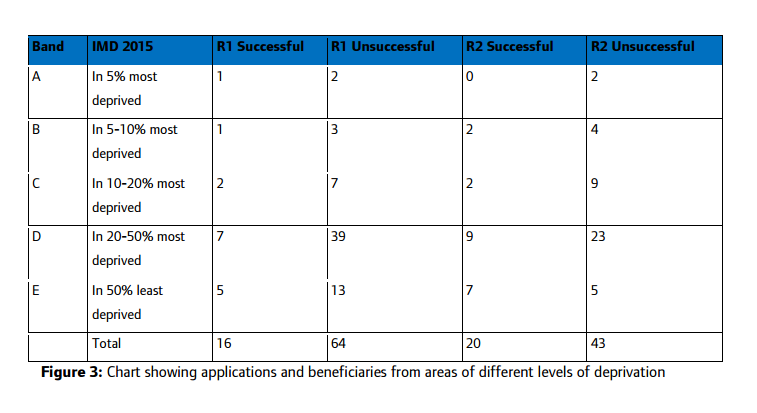

The reliance on capital or pound-based voting (Bernholz et al. 2016) – though to a lesser extent, existing capacity – subsequently means that successful campaigns and projects are more likely to emerge in wealthier areas. This can, to some extent, be noted spatially across London, where applications were least common from groups in London’s most deprived areas, based on an Index of Multiple Deprivation (figure 3). Through involvement in the crowdfunding process, public bodies should, in theory, be able to exert a certain amount influence and support for applications from more deprived areas, either through directing funds to campaigns based in areas with higher deprivation, or providing more support or expertise where necessary. Interestingly, of all projects that have applied to the Mayor’s hive, only those which have been backed by the Mayor have reached their target. Thus the amount of wealth in an area (shown through backers) seems to matter less to success than the Mayor’s contribution.

It should be noted that in the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme, more projects are delivered in the 50% most deprived areas than 50% least deprived areas of London, and this needs to be upheld and developed as the programme progresses. At a finer-grain however, the most deprived areas (band A and B), do appear to suffer from disproportionate disinvestment through the Programme. Perhaps most interestingly is the apparent peak in applications and successful projects in band D. More research is required to fully understand the driver of this peak. One possible explanation is that within band D there are many high growth areas, including pockets of Dalston, Peckham, Camden Town, Aldgate, Walthamstow, Tulse Hill, Vauxhall, Crystal Palace and so on, in which a new and changing community brings with it skills, capacity and wealth that may not have existed previously.

Read the full report “Understanding the social impacts of the Mayor’s Crowdfunding Programme” here.